*Last updated May 2021 by Eric Chan, ND

Navigating testing in suspected lyme disease and the approach I use for most patients

Testing is a changing field in working up the possibility of symptoms being related to current or previous lyme infection. With the advent of increased awareness about the condition in general and recently the more readily availability of different testing methodologies from a variety of labs, it can be a confusion picture when information is sought beyond the standard two-tiered testing in acute lyme.

For many patients there is a basic relatively cost-effective approach that can be utilized. Testing is a complex process that can help to guide to find the most appropriate therapy. Testing is selected based on the history, exam and presentation of the patient. From a naturopathic perspective, it is just as important to evaluate the terrain of the patient in order to restore balance to physiology. The foundations of health need to be present, including most commonly optimal anti-inflammatory diet as well as sleep, support for weakened systems including assessment and removal of toxins (sometimes metals, solvents / organic toxins, and biotoxins such as mycotoxins from mold). Testing for exposure to and active infection is one component of the process.

Back to the lyme testing options...

The usual testing for lyme disease in the conventional world is two tiered testing. It is testing for antibodies against lyme. Antibodies are proteins the immune system makes against foreign structures, including lyme and associated infections. They are classified as humoral immunity and come from B cells. The combination of an ELISA, or IFA and then a western blot is done. In these tests, we indirectly test for lyme by seeing if there are any antibodies in our blood that react with whatever strain of lyme the lab is using. That part is bolded because it really spells out the difference between labs. Most if not all CDC labs will use the B31 strain of lyme, whereas other labs will use that plus another strain or more lyme proteins, depending on the lab. The latter do this to try and increase sensitivity, or likelihood of picking up exposure to the infection.

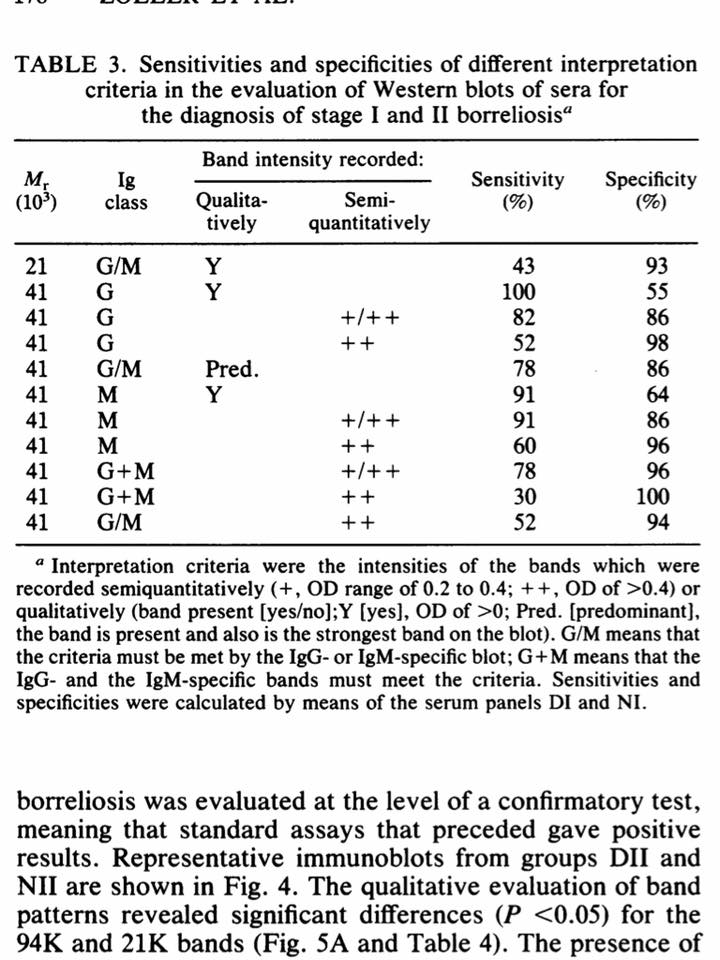

There is also interpretation criteria with this type of testing. For example, CDC would consider an IgG western blot positive if there are at least 5 bands (or antibodies) against a group of selective lyme proteins exists. 4 is considered non reactive. Other labs will use their own criteria and say perhaps two are needed, depending on how specific the protein is against lyme. (Research does support the latter - see Zoller et al where even just a 41 kda antibody, if very strong, was very specific against lyme... published in the 90s. Mavin et al, in Interpretation criteria in Western blot diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis, British Journal of Biomedical Science also described alternate criteria in which fewer bands may be interpreted as an equivocal or weak positive result, suggesting at least retesting in the future or a trial of treatment and then testing.) The advantage of conventional two-tiered testing is fewer false positives, while the advantage of alternate interpretration criteria of the above is that we may catch more patients who have this history.

Zoller data:

Mavin data:

I also use very frequently the Elispot testing, which is an assay that assesses the other side of the immune system, namely the T-cell reactivity against lyme. Here, if the patient does not have a very strong antibody response and their testing from ELISA, or western blot is negative, sometimes we can get valuable information from the T cell assay as to whether or not this side of the immune system is suggesting lyme infection.

I also use this test to try and quantify whether there is still substantial lyme-related inflammation or infection that is persisting despite current treatment protocols. As an example, a patient may have made great progress on the herbal or drug antibiotic approach, but has certain lingering symptoms in which we are not clear as to whether they are related to residual infection. Perhaps their elispot was a moderate high positive before - in this example, sometimes their lyme elispot may now be negative but a coinfection elispot may be moderately high, indicating a different treatment course. The testing may all be negative, further reinforcing the fact that consideration of infection alone is not enough, and due course and effort must be given to other factors as well.

I also see a substantial number of patients whom have already seen other practitioners and undergone basic lyme treatment, yet may have not had much benefit. If after re-evaluation of their case, and excluding other diagnoses, we feel that chronic infection is still a likely diagnosis, then often times elispot testing for lyme, and common coinfections (based on history) can help to guide if there is still untreated infection in which we could modify treatment courses. In this scenario, we also evaluate the common roadblocks to cure, eloquently described in Dr Richard Horowitz' book "Why Can't I Get Better." This may include adrenal assessment, thyroid assessment, heavy metal testing, amongst other common lyme-induced changes and/or post lyme changes.

In the majority of cases, non-antibiotic approaches can be very useful in such cases which includes ensuring foundations of health are present such as diet, sleep, micronutrients; toxins are removed including metals, organic toxins and mycotoxins; immune balance is restored including cytokine balance, c3a, c4a; and stimulation of the body’s natural healing has occurred including ozone therapy.